2012

Renata Tassinari: Painting the Box- Paulo Venâncio Filho

Galeria Pilar e Lurixs Arte Contemporânea

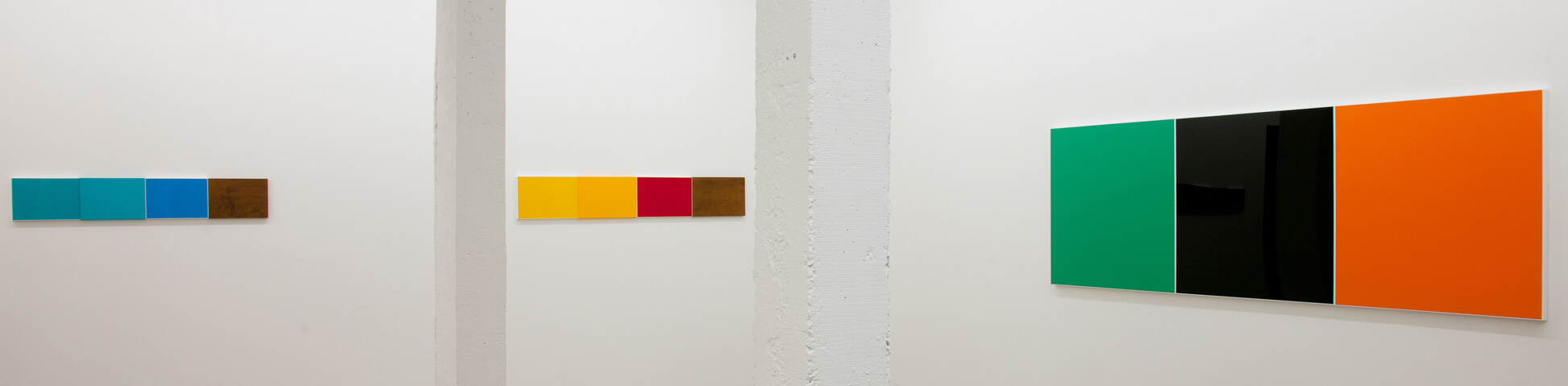

Renata Tassinari’s current painting is composed entirely of squares and rectangles, always. It is a whole always divided into squares and rectangles. The canvas is divided into equal parts. This is quite a simple method, but raises the question: is it a combination of parts or a whole divided into parts? Or, still, is it a single surface or a collection of surfaces? What can be said is that the parts are heterogeneous, almost incompatible, and even antagonistic: painting, acrylic, and wood. The clear presence of paint, the transparency of acrylic, and the discreet opacity of wood, stand together, side by side. All in all, the result could have proved disastrous. But the subtle dialogue between the qualities of each part suggests a highly cultured conversation that incorporates an already considerable experience of painting. These are not simply experiments, or conceptual projects, even if they are a bit of both, enlisted in an exploratory program of painting of/from today, that which lies before you.

Wood and acrylic; these presences, hardly customary in pictorial space, arouse immediate attention. By appearances, there is nothing as different from painting as the neutrality of acrylic. How does one bring together, without awkwardness, an acrylic surface, synthetic and cold, with the expressiveness and materiality, however minimal, of painting? How does one effect this combination, paradoxical and yet contemporary, without submitting one to the other?

Detaching acrylic from banality, from vulgar utilitarianism; a desire to prove that, in art, there is no material that cannot acquire plastic relevance.

To begin with, I imagine that Renata Tassinari treats acrylic, despite its transparency, as an obstacle. A transparent obstacle: another potential paradox that presents itself. At first, acrylic seems to be among those surfaces that expel and repel painting; on the other hand, it is frequently used in frames, determining the limits of a picture. Acrylic can be above, below, beside, but not inside, so that we could include this procedure of Renata’s among those that, in the long list accumulating since the beginning of the 20th century, tried to bring sundry elements from the real world into pictorial space. But the transparent surface of the acrylic, through which one sees the painting, together with reflections of the surrounding environment, suggests another canvas, not only that of painting. If this reasoning makes sense, we enter the domain of current experience in the digital world, where reality and image merge in the Screen, understood here in the double sense of painting and projection screen. Hence, also, the double identity presented by the work: painting and box. Painting the box, we could call it, like the image on the monitor. A box whose limit is a physical, not optical, hard-edge. Which makes this painting an almost-object, or an object-almost-painting. For it is that "almost" that gives interest to the experiment. The immediate sensation is that of something ready, that even comes in its own box. A briefcase-painting, in the sense of portable, so to speak, that we wish to take away with us, under the arm.

Like the acrylic, the wood laminate that appears in some paintings, a cutout of both substance and surface, also refers to the most traditional material used in frames. The fusion of an object with its frame, more than an appropriation of frame by painting, introduces a certain conceptual component, a meta-pictorial inquiry, discreet but latent, that goes beyond the plastic. A possible game of semantic and syntactic possibilities is triggered within the elements of the picture. Is it an extension of the frame onto the surface of the picture or an opposition between two surface qualities? Or both, at once? In fact, the grain of the wood, the veins and knots, suggest a tromp l'oeil while emphasizing the character of the picture as object. However, these opposing operations are absorbed, as it were, by the serene visual architecture that regiments them. This painting seems to reflect upon the contemporary visual stridency that strikes us in all spaces, public and private. A stridency manifested in the current proliferation of screens. These days, there is no escaping the screen, the ubiquity of the screen. Not only the screen as monitor but the images, incessantly appearing on the screen. So, cleansing the screen may well be the strong desire of this painting. But cleansing in a singular manner: cleansing with colors. Cleansing with clean colors. It is as if they come already wrapped, untouched, pure. The color in the painting simulating the virginity of new things, still unused, absolutely ready-made in appearance. Its decorative power, that we could call Matissean, so intense in Renata’s trajectory, may impose a resolute practical scheme, almost a chromatic ready-made. Resolutely monochromatic, minimal in their expressivity, clear and serene, the colors also seek convergence, coexistence; the tonal differences are reduced, and the contrast, where it exists, is still a consonant chord.

One cannot avoid associating this painting to the architectural surfaces that house us. Acrylic, paint, and wood, are they not also a kind of reconfiguration of window, wall, and floor? And the squares and rectangles, do they not also stand in relation to the most common architectural spaces we inhabit? So, here we have painting that is as constructive as it is "construction," one congruent with constructed space. Just as architecture uses materials with disparate qualities, so does this painting. And the discreet consonance that it effects between the discordant elements of chaotic contemporary space, cutting out and recombining simple elements, suggests a model of how to inhabit the surface of the picture. Looking is also a way of inhabiting.